He was cruel to her, harsh and

spiteful. Yet he had given her the

greatest happiness she had ever known – in a world he made

himself.

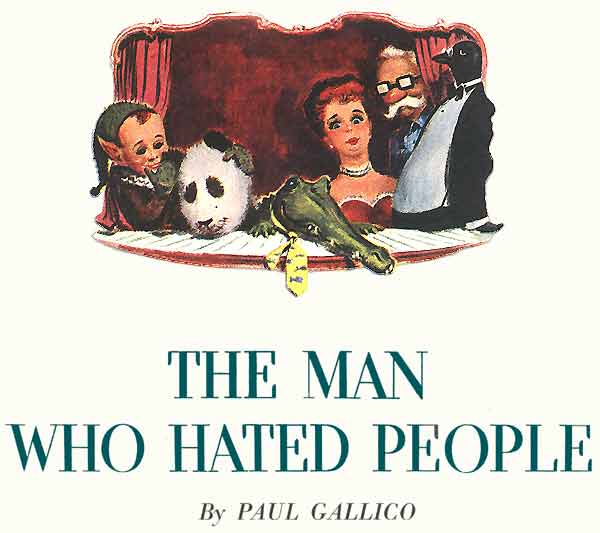

HAUNTING melody played on a

flute, a kind of nursery rhyme in music was heard just after the

clock struck six; the lights went out in the living rooms of

three quarters of a million homes of the East and Midwestern

video zones; young and old settled before their television sets

as the curtain of the puppet booth on the screen rolled up,

revealing the upper half of a small, impish-looking leprechaun

with pointed nose and pointed ears, and his companion, a fat,

comfortable and slightly lazy-looking panda. The Peter and Panda

show was on the air.

HAUNTING melody played on a

flute, a kind of nursery rhyme in music was heard just after the

clock struck six; the lights went out in the living rooms of

three quarters of a million homes of the East and Midwestern

video zones; young and old settled before their television sets

as the curtain of the puppet booth on the screen rolled up,

revealing the upper half of a small, impish-looking leprechaun

with pointed nose and pointed ears, and his companion, a fat,

comfortable and slightly lazy-looking panda. The Peter and Panda

show was on the air.

Soon the other characters in the never-changing cast would appear, compounded of the lights and shadows flickering across the iconoscope tube: Arthur, a raffish crocodile whom everybody loved, but no one dared trust wholly, for he was not entirely honest; Mme. Robineau, a French lady of indeterminate age with dyed hair, who had her memories; Doctor Henderson, a penguin with a rather exaggerated opinion of his own importance, and who, according to Milly, was the only person she had ever known who carried his own stuffed shirt around with him; and a certain Mr. Tootenheimer, a toymaker, who could repair practically anything that was a little bent or broken, including human hearts.

And then, of course, there would be Milly, the sweet-faced girl with the slightly harassed expression. She was the only visible human being who appeared on the program. She would sidle into the picture in response to pleading or frantic or conspiratorial cries of “Oh, Milly – Mil . . . can you c'mere a minute?” from one or another of the little people who inhabited this phantasy world.

On this night, then, the lights were low in farm, city and suburban homes, but there was an odd kind of tension present in the onlookers as the half hour of puppet play passed before their eyes. All the little characters had been plying Milly with questions as to her engagement and forthcoming marriage to a man named Archer. There were few in the audience who did not know that Milly was quitting, and would not appear any more.

In a darkened home, a child asked insistently, “But why does Milly have to go away and marry someone else, when it's Peter, Panda and Arthur she loves better than anyone?”

In a club, an elderly man seated before a console model said to his companion, “Damn silly, but it gets you. It isn't written, you know. It's all ad-libbed. Brilliant fellow, an odd character by the name of Crake Villeridge, does all the voices and manipulates the dolls. The girl's learned how to work with him and the two of them make it up as they go along. Pity she's leaving the show.”

Elsewhere a neglected child sat before a set and cried his heart out. In this phantasy for the past two years Milly had been his real mother and he loved her better than anything in the world.

The program continued. Arthur the crocodile and Milly were on. Arthur said to Milly in his peculiar, raspy, confidential voice, “I've got a going-away present for you.” He ducked down and came up with an alligator handbag in his jaws, set it on the ledge of the stage and tilted his head speculatively. “Awfully familiar,” he remarked. “Someone I must have known somewhere once.”

The harassed and worried expression known to millions came over Milly's face. “Arthur! Oh, dear, you shouldn't have.” Her tone was both alarmed and protective. “Arthur, you come right over here and tell me where and how you got that.”

“Aw, Milly – must I?”

“Arthur – ”

By a twist of his neck Arthur managed to look hurt. “I'm buying it–on the installment plan.”

“Oh? And what happens if you can't keep up the payments?”

“I made a little deal.”

Milly faced him and her smile was half tender, half commanding. “What kind of a deal?”

“Well, if I can't keep up the installments, the man is to get something else in exchange.”

Milly walked into the trap. “Yes, and what is he going to get in exchange for this beautiful bag?”

“Me,” Arthur concluded.

Milly turned her head for an instant and looked out over the audience. The sensitive eye of the television camera picked up a curious trembling about her lips, and then, twice, blinding shafts of light splintered from her cheeks like tiny exploding diamonds. She turned quickly back to the crocodile. “Oh, Arthur, dear – I don't know what to – “

Like a flash, Arthur whipped his green, scaly head beneath her chin, and snuggled there twixt neck and shoulder in the manner of a child that takes immediate advantage of tenderness.

The show ended on a curiously inconclusive note. All of them, Peter, Panda and the rest, had said good-by and vanished beneath the counter of the stage, leaving Milly alone before the booth, facing the audience, twisting her fingers nervously and looking miserable as she said, “I – I don't know what I shall do without them all.” She appeared about to say more, but the half hour was up and the scene faded into the final commercial, followed by the nursery melody.

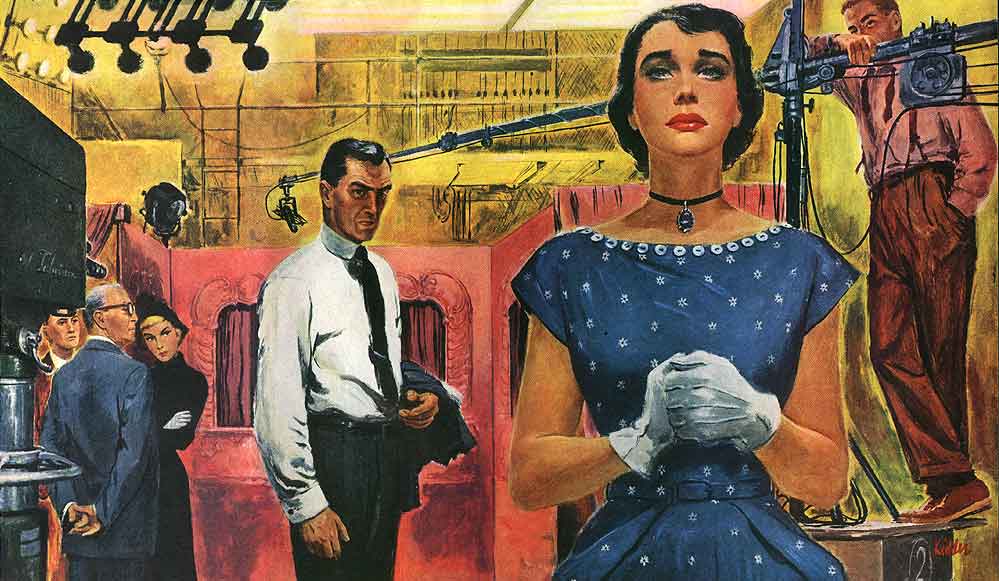

Millions watching felt a sense of loss as though a family close to them were breaking up. Milly, carrying her own heartbreak away from the familiar Peter and Panda set, picked her way over the lines of light and camera cables on the floor of the National Television Network Studios and went the long way around to her dressing room. She could return the same way later, as Stage 1 was scheduled to be dark for several hours. Above everything she wanted to avoid a meeting with Crake Villeridge. It was all over and done with now. She had freed herself forever from the power of his dark spirit and lacerating tongue to hurt her.

It was a relief in a sense. When she had creamed the make-up from her face and changed into her street clothes, she would cross that musty-smelling stage for the last time and go out onto a Fifth Avenue bright with the electric city twilight.

At her side would be Fred Archer, a plain, simple man who loved her, who was offering her his devotion and himself, and taking her out into the light of normalcy. In exchange for this and her freedom she would cherish him and make him a good wife and give him what he seemed to desire most – herself.

It was over then, at last. An end to the bitter, snarling reproaches, the biting, sarcastic tongue, and the awful, hour-long rehearsal of songs and musical numbers with a man who was a great artist, but a misanthrope.

In front of the technicians, directors and everyone he would shout at her, trying to humiliate her.

She remembered how it had all begun two years ago with the strange audition in Studio K. The nervous girls, the applicants for the queer job of straight man to a pack of puppets, were ushered in one at a time. When the door had closed on Milly she found herself in front of an empty puppet stage. There were strange whisperings beneath and behind it.

A leprechaun had popped up from below finally, or rather half a one, for it was a glove puppet and had no legs. He stared at Milly for a few moments and then called down backstage,

“Hey, Pan!”

“What's up, Pete?”

“There's another one here.”

“ Coming right up.”

The panda appeared, fat, wheezy, comfortable and not too bright-looking. “Phew!” he sighed. “This is a day. How many more of these do we have to inspect? This one's got nice eyes.”

“Do you think so, Pan? Her hair looks kind of mud-colored to me. Otherwise she's not a bad-looking lass. Legs aren't too good, but it doesn't matter. They won't show.”

Milly had had all she could take. She stamped her foot and cried, “How dare you two stand there and discuss me! Don't you know that's the worst manners?”

The leprechaun said, “I

dunno, maybe so. We've all been running kind of wild of late.

Maybe what we need is a strong hand. Still, I don't know what

you're getting so huffy about. It's you who are wanting the

job.”

The leprechaun said, “I

dunno, maybe so. We've all been running kind of wild of late.

Maybe what we need is a strong hand. Still, I don't know what

you're getting so huffy about. It's you who are wanting the

job.”

Milly said indignantly, “I'm not so sure now.”

The panda said, “Oh!”and looked baffled. “Perhaps we'd better talk this over, Pete.”

They both vanished beneath the counter.

They were replaced by the head and neck of a crocodile. The croc had a leer in his eye and a worse one in his voice. He graveled, “Hello, kid,” at Milly.

She came over to the booth and said, “Don't you 'hello' me. You're a wicked scoundrel if ever I saw one.”

“I am not. I can't help my looks. Come over here and try me. I won't bite. Put out your hand.”

Milly put out her hand gingerly. On her face there was a look half worried, half charmed.

Her brow was furrowed a little. The crocodile gently snuggled his chin onto the palm of Milly's hand and heaved a deep sigh. “There,” he said. You see how you misjudged me?”

Milly had never been one to be deceived by obvious sanctimony. She said, “I'm not so sure I have at all.”

“Heart like a kitten,” the croc said, snuggling his chin a little deeper into the warm cup of Milly's palm, and then added, “But only time will tell. Can you sing?”

“Of course I can sing.” Milly replied. “Can you?”

“Not very good,” the croc admitted. “But I've got a pal. He has a swell bass.” He called down, “Hey, doc.”

A penguin appeared. He wore pince-nez attached to a black ribbon. The crocodile introduced him. “This is Doctor Henderson. Forgive him being formal. He's on his way to a meeting of the Franalogical Society. I didn't seem to get your name. Well, anyway, mine's Arthur.”

The penguin bowed and said, “Chawmed, chawmed, chawmed.”

Milly made a little gesture of shifting something on the counter of the stage. “Let me help,” she said, “the needle's stuck.”

“Delighted!” concluded the penguin. “Shall we sing Three Blind Mice? Such a lovely sentiment.”

Without waiting for her consent, a hidden piano struck up the melody, and Milly found herself singing. Arthur, it developed, had a clear and resonant baritone when he opened his jaws wide.

Doctor Henderson came in occasionally with basso “Poom-pooms.” Milly was trained and musical, and their voices blended harmoniously.

A dinner bell suddenly interrupted them in mid-song.

“Oops!” said Arthur, bringing his jaws together with a snap. “Sorry! Chow! So long, kid!

Come on, doc.” They vanished beneath the counter.

Their going left Milly with a momentary sense of forlornness. Another character appeared. He reminded Milly of Hans Sachs, the cobbler of Die Meistersinger. He had a most kindly face and friendly expression.

He stared at Milly for a moment and then said with a thick Weber and Fields accent, “My name iss Herr Tootenheimer. Se audition iss ofer. Se poss says you are hired. Come to Room 427 at fife o'clock.” His head inclined in an odd way that struck Milly as a sort of benison. “May I zay I am hoppy? I sink perhaps you are a sveet child.”

He disappeared, leaving Milly alone with a sense of enthralling happiness. Not even the meeting in Room 427 later that afternoon could dispel the sense of enchantment.

There was a Mr. Ryerson there, a short, blond, nervous official who was the technical manager of the show; and standing over in a window looking out onto 50th Street, a tall, gaunt man with a fierce beaked nose and the blackest hair Milly had ever seen. His clothes hung loosely on him.

Ryerson said, “Well, now, Miss Maynard. This is Mr. Villeridge, Crake Villeridge, the – ah – creator and – producer of the show. Your performance his afternoon came closest to what he wants.”

“But,” Milly said, “it actually wasn't a performance.”

“Exactly,” said the tall, gaunt man, and in his voice Milly heard the deep resonance of the trained singer. Then he turned away from the window and Milly could see the other side of his face. Try as she would she could not repress a little gasp of shock at the injury that had been done to it. There were two crisscross scars from temple and brow, to chin. They traced lines of damage to his left eyebrow and lid, which drooped harrowingly and altered the slant and line of his jaw, giving him an expression of evil.

He was well aware of the horror she felt. He repeated harshly, “Exactly. The first time you start giving a performance, you're through. We will rehearse the songs for the evening at ten in the morning in Studio K, for one hour. At that time I will give you the general line of the show. From then on, you're on your own. You will pick up your cues from what is said and done. If you can take it away and go with the pack, they will follow you. That's all.” He stalked out.

Ryerson said, “Crake's all right. You'll get used to him, Miss Maynard. He's had a rough deal. He's a French Canadian, you know. Was going to be quite a hockey player. One night there was a mix-up in front of the goal and he fell. Two men skated over the side of his face. He was lucky they avoided the eye. He's had five operations. It broke up his career.”

Milly had the most muddled feeling. With whom then had she been conversing upstairs in Studio K? Had all those voices and personalities been Crake Villeridge? Never at any time in their long association did she completely get over this feeling of strangeness and confusion.

At first, it had seemed

easy, for it was just as it had been when Milly was a little

girl in St. Louis and had indulged in long and complicated

dramas with her dolls, all of which had different characters,

with Milly making up the dialogue for every one as she went

along. Now the dolls all had minds and tongues of their own.

At first, it had seemed

easy, for it was just as it had been when Milly was a little

girl in St. Louis and had indulged in long and complicated

dramas with her dolls, all of which had different characters,

with Milly making up the dialogue for every one as she went

along. Now the dolls all had minds and tongues of their own.

And in spite of the fact that she was grown up and a television actress with a promising career, Milly simply continued to play herself. She was tomboy-companion, coconspirator, teacher, nurse, mother and sweetheart to them all.

But later it seemed to her that the scenes that took place at rehearsal and after the show in the studio were continuing nightmares from which she could never seem to awaken. In front of sound men, electricians, cameramen, assistant directors and friends of the sponsors milling around the set after the telecast, he would shout at her, “What the devil do you mean showing up with your hair all frizzed up that way? Why don't you leave it alone the way it was?”

Or, “You call that thing you're wearing a dress?” And, “Why did you take the lead away from Arthur and throw it to Panda in the second half?” It was Arthur's sequence.”

“Because Panda looked so forlorn and helpless, standing there with everybody against him. Oh, Crake, for heaven's sake, give me a script and I'll follow it.”

“Don't talk like a fool. There'll be no script. If you haven't learned to know your characters by now – ” Crake would stalk away, leaving her standing there, miserable.

But the next night she would return to the half hour's journey through Fairyland, where little people came alive and brought her their troubles and problems, or cuddled, or were sweetly impudent and made her laugh.

Of these, Peter, the leprechaun, since he considered himself immortal, was the most independent, while Panda and Arthur seemed to need her most. Doctor Henderson, she learned, was the complete, pompous bore, and yet, for all his stuffed-shirtism, there was something likable and reliable about him. And in Madame Robineau, the French lady of uncertain age with dyed red hair, she found an unexpected ally of great sympathy and understanding. She had buried a number of husbands and seen the world. When the boys ganged up on Milly, as they sometimes did, she would appear to help restore order and counsel Milly with her well-known aphorism, “Well, my dear, that's what men are like. You cannot have everything in life, you know.”

Most comforting of all was old Herr Tootenheimer, the toymaker, with his sweet, simple and deeply felt philosophies which could heal any hurt or resolve any situation or entanglement in which they managed to bring themselves. His appearance on the puppet stage was always for Milly a kind of sweet release from nervous tension.

But it never seemed to last, once the red lights had gone out on the telecameras and the show was over. Sooner or later, Villeridge would have another vicious outburst of temper against Milly.

A month ago he had emerged pale and furious from the puppet booth and shouted at her, “Milly, what the dickens is the matter with you? You haven't developed story decently for three days. You're absent-minded and distracted, and wandering. Are you in love or something? If so we'll thank you to keep your private emotional shortcomings off this program. You'll either give us everything you've got or else. . .”

It had touched a weak spot. It was true that Fred Archer had been unusually kind and persuasive, and perhaps she had thought that she was a little in love with him. He was such a contrast to Crake Villeridge and the way he treated her.

Her nerves had snapped, and in an angry scene, she had accepted the . . . “or else,” given notice of resignation and announced that she was going to marry Archer. She thought she would never forget the look that Crake Villeridge had turned upon her, the fearful play of light and dark, good and evil, that crossed the poor, damaged features.

The gossip columns first, and then the rest of the press had of course got hold of the fact that the famous Milly of the Peter and Panda show was leaving the cast for good, to get married.

During the course of the month's notice Milly had given, there were letters of protest, interviews, speculative stories, and no peace.

The last show of all had been harrowing. For the little people, the characters had harped and harped. They all took turns in twisting and bending and testing out her heart. They asked her what her new husband-to-be was like, how much she loved him and where they would go to live together, how it felt to be happy, whether she would be having children of her own now and what they would be like. And whether, when that happened, she would then forget all about them.

No one who saw that show would ever forget Milly standing at the side of the puppet booth, wringing her hands and crying, “Oh, no, no! I can never forget you. You will always be like my own children and as dear to me.”

Milly finished changing into her street dress. Well, it was all over now. For two years she had been living in a phantasy world that bordered on a kind of sweet and calculated madness. She was on her way back to sanity now. She cleaned out her dressing room of her belongings and packed them in a small suitcase. Now she looked around for the last time, snapped off the lights and went out the back way down the long corridor that would lead across the deserted studio and thus avoid passing Crake's office or the lobby where he might be waiting for her with one last attack.

Stage 1 was in semidarkness. Milly waited for a moment to let her eyes accustom themselves to the gloom and then picked her way carefully past the massive cameras, microphone booms and the network of wires and cables on the floor. She passed close to the silent, empty puppet booth, but her gaze was straight ahead.

A gravelly voice said, “Oh, Milly.”

Milly jumped and gave a little shriek. “Oh!”

“Here I am.”

She stared into the darkness. “Arthur!” She could see him now. He was huddled on the counter or stage of the booth, 'way at one end, quite flat, his chin on the board, like a dog that has been beaten. His beady glass eye was contemplating her warily. “Arthur,” she repeated, “what are you doing here? Where are the others?” After two years, one fell into the habit of reply. One could not help oneself.

“They went. I stayed behind. Milly, take me with you.”

Milly felt as though a stone had lodged in her heart, weighing her down. She wanted to flee and could not. “But, Arthur, what about the others, Peter and Panda and Mr. Tootenheimer and Doc Henderson and all the rest of your friends? You can't leave them.”

The wary figure of the crocodile moved a little closer to where Milly had paused at the side of the booth where she always stood. “Yes, I can. I don't care. I want to go with you.”

“But, Arthur! Isn't that disloyal to the others?”

The croc seemed to think it over for a moment, then came over and just barely nuzzled the tip of his chin on the back of Milly's band and sighed deeply. “I know. What's the dif? Everybody knows I've got a touch of jerk in me. I never know where it's likely to butt out next. Look after me, Milly.”

Milly's throat felt

tight and constricted. Her head was swimming. A fat, lazy voice

said, “Oh-oh. Is that you, Art? I thought you'd gone home.”

Milly's throat felt

tight and constricted. Her head was swimming. A fat, lazy voice

said, “Oh-oh. Is that you, Art? I thought you'd gone home.”

“I thought you had, Pan. Listen. Milly's here.” In the gloom, the girl saw the white mask of Panda rise above the counter. The two held what appeared to be a whispered conference for a moment. Then Arthur said, “Okay, Pan, see what you can do with her,” and vanished below.

“Milly,” Panda whispered. “Don't go away.”

“Panda, dear, I must.”

“Then take me with you. I'm too young and stupid to be left alone.”

“Pan, you mustn't say that. You can be as clever as – ”

Milly, I'm frightened.” He commenced to moan as he did sometimes when things became too much for him.

“Ah hum! Har-r-r-rumph! Come come, young man! No exhibitions!” It was Doctor Henderson, the penguin, in formal attire as usual. “Ha-hoom! Just going to a dinner,” he excused himself. “Milly, I wish to say – that is – it seems to me – but on the other hand – Bless me, I'm afraid that words fail me. To think that this should happen at a time like this. Ah-hoom. Bless me!” The pomposity suddenly left his voice and he said quickly, “You'll need someone to help look after you. Willing to drop everything and offer my services. Think it over, Milly, my lass.” Then he, too, was gone.

For an instant the stage was bare and then Milly was aware of a familiar, gay, light-hearted whistle, the theme of their show. It was Peter, the leprechaun. He bobbed along the length of the counter once and then said, “Hi, Milly. You still here?”

Milly suppressed a sob. “I was just leaving,” she said.

“'Tis going to be queer without you,” the leprechaun said. “Very queer. But maybe now I'll be able to go places. You know, you were always holding me down, Milly.”

“Peter!” Milly said. “I never did. I always wanted you to – “

“ – fly?” Peter concluded. “I wonder. But maybe I'll be able to, now that you're going.”

Sudden tears blinded Milly's eyes. “Yes,” she whispered. “Fly then, little Peter. Fly.”

The puppet emitted a mortal wail. “But I don't want to fly. I only want to be with you forever. Take me along with you.” He bounced over and settled his head and shoulders into the hollow of Milly's neck. “But you don't love us, Milly, not really!”

Something between a groan and a sob was torn from Milly. “Oh, I do! I do! I love you all. It is only him I hate so terribly, so desperately.” She shuddered to the touch of the object cuddled close to her neck. It made her wish to weep endlessly. And then that, too, was gone.

“Hello, Milly.”

She looked up. Now it was Mr. Tootenheimer, the toymaker, who was regarding her benignly from behind his square-rimmed spectacles. He began to speak to her in the calm, sweet, comfortable, friendly voice of the old philosopher, with but one odd difference of which she was not immediately aware.

“Yes, Milly, it is true. You hate him dreadfully. And you do love us all. I believe you. Every one of us has a place in your heart.” He paused, cocked his head a little to one side and then asked the question that Milly had never dared face. “But who are we all, my dear – Peter, and Panda, Arthur and Doctor Henderson, Madame Robineau, and even myself?”

Milly stood quite still and with one hand held tightly to the side of the booth, for the floor of the studio seemed to be swaying beneath her. It came to her that Mr. Tootenheimer had somehow lost his accent.

“A man may be composed of so many things, Milly, and be so many different persons. He can wish like Peter to disregard the rules of the earthbound and fly, and this will be offset by the lazy, indolent, timid and not quite bright Panda in him. Part of him will be a thundering bore and a stuffed shirt like Doctor Henderson, and part of him a little bit crooked, snide and double-dealing, like Arthur, if the opportunity presents itself. He will be balanced perhaps by the philosophy of myself, or the femininity of Madame Robineau. Every man has a touch of Madame Robineau in him. And each of us has given you his heart. I think I even heard Arthur offer to lay down his life for you, earlier this evening. Or, his skin.”

“No, no; no more,” Milly cried. “Stop.”

But Mr. Tootenheimer went on: “And a man who had been cut and scarred and was ashamed of his appearance, who loved you from the first time his eyes rested upon your face, could be a brutal fool, believing that if you could be made to love all of the things he really was, you would never again recoil from the things he seemed to be. He failed. And yet – and yet – ” And here the puppet that was Mr. Tootenheimer seemed to be looking right into the soul of Milly through the square-lensed spectacles. “Whose hand was it that lay so often and so trustingly in the hollow of your neck, to which you gave yourself and did not shrink or recoil from it? Have you lived only in the phantasy world we created? And even there, if you could learn to love each of us for what we were, might it not mean that sometime you could come to – ”

“Crake”' Milly cried; and again “Crake! For God's sake, come to me before I lose my sanity forever.”

Then he was there beside her, looming enormous and terrifying in the semigloom of the corner of the empty stage, but in the darkness she could not see the scarification of his face at all, nor ever would again. She swayed toward him and he caught her and held her to him with such love, longing and hunger as she never knew existed.

Fragments like clouds drifting across a summer sky wandered past the peace and sweetness that enfolded Milly.

The outside world – reality – Fred Archer – good-by to them all. Fred would be hurt, but engagements had been broken before and he would come to understand. Her lot lay with the enchanted Never-Never Land of the mind, its children who had come to be a part of herself, and the man who was the creator and father to them all.

“Milly,” Crake Villeridge whispered “You called me.”

“Sh-h-h-h-h-h,” said Milly softly. “Tell Arthur, and Peter and Panda, tell them all that I will take them with me forever.”

THE END