Kukla was

invented to express a shy young man's undying devotion

to his love.

But today it's Kukla

who's receiving the undying devotion - and he's not at

all shy about it!

Kukla was

invented to express a shy young man's undying devotion

to his love.

But today it's Kukla

who's receiving the undying devotion - and he's not at

all shy about it!

Don't, if you want to keep peace with that circle of fans which grows each time television penetrates a new city, ever call Kukla a puppet, nor Ollie anything than a dragon.

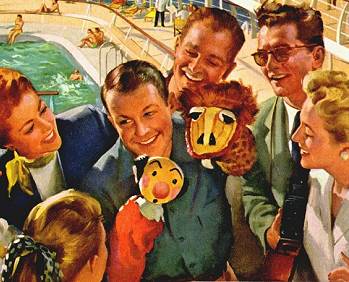

Their friends, trying to explain NBC's Kukla, Fran and Ollie to one who lives beyond the television horizon, start by saying Fran is Fran Allison, whose wit and charm match her beauty. Then they stutter. While conceding Kukla and Ollie are, in substance, cloth and cotton, friends hate to come right out and call these intriguing personalities puppets.

To a wide variety of people, they are

real.

To a wide variety of people, they are

real.

They are real to the five-year-old who streaks in from play. They are real to business men who stop work to watch. They are real to Chicago's Mayor Kennelly. His Honor expressed public regrets when Ollie fell into a lagoon and offered to have the lagoon filled in.

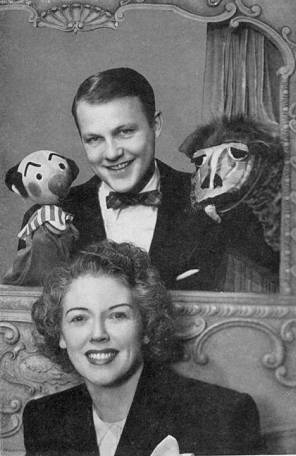

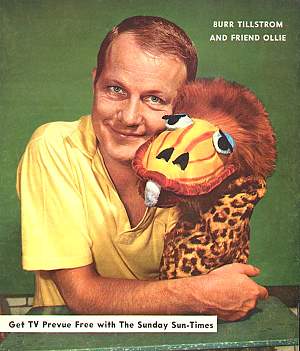

To most viewers, Kukla and Ollie are as real as Fran, their co-star, and much more real than their creator, Burr Tillstrom.

Viewers glimpse Burr for only a few seconds at the close of each show when Kukla, - beckoning in a young man with unlined face and crisp crewcut, says, "Thank you. Thank you on behalf of our boss, Burr Tillstrom."

Many, including Burr himself, will argue that "boss" business. Burr says he works for Kukla. With a million dollar, five-year contract just signed, it's quite a job.

Fans, when they emerge from illusion far enough to realize Burr is the person and Kukla the puppet, ask questions. Who, they want to know, does the voices? Is Fran a ventriloquist? Who writes the script?

The answer, briefly, is that the Kuklapolitans are Burr and Burr alone. He plots the show. Fran and the rest of the staff help dream it up, and then it happens, spontaneously. Burr and Kukla have grown up together. Together, they have produced joy and laughter, but they have also faced sorrow, hunger and death. It's the living they have done which makes Kukla Fran and Ollie more than "just another puppet show."

Their story starts with Dr. Burt F. Tillstrom, a chiropodist, and his wife, Alice, whose sons were Dick and Burr. The kind of parents who thoroughly enjoy their children, Burt and Alice took the boys swimming, sailing, hiking. They also had an interest in amateur theater, and Burr mimicked them by having his teddy bear, toy soldiers and giraffe act out nursery rhymes and songs his mother sang.

During

summers spent at their grandparents' homes in Benton

Harbor, Dr. Tillstrom provided additional stimulus for

the boys' quick imaginations. The moment he

arrived for week ends, Dick and Burr pounced on him for

stories. Some he read from Peter Rabbit, Alice in

Wonderland, and the Wizard of Oz. Others he made

up during long walks through open country.

During

summers spent at their grandparents' homes in Benton

Harbor, Dr. Tillstrom provided additional stimulus for

the boys' quick imaginations. The moment he

arrived for week ends, Dick and Burr pounced on him for

stories. Some he read from Peter Rabbit, Alice in

Wonderland, and the Wizard of Oz. Others he made

up during long walks through open country.

As early as that, the Kuklapolitan Opera began to shape, for Burr, on his return to the city, endowed his toys with the characteristics of his country friends.

Eventually, puppets replaced toys and the chain of circumstances began which inevitably turned Burr Tillstrom into a puppeteer.

It was marionettes, however, which brought him his first job, right after high school graduation. Those were depression days, and the Chicago Park District and Federal Theater joined to set up a marionette group as a WPA project.

Burr and a few other puppeteers, not on relief, were hired as instructors to help get the show on the road. For the sheltered lad from a substantial home, it was an awakening. Burr's blotting paper mind soaked it all up and he added their skills and experience to his own.

And that included hunger. He has never forgotten the shock of opening a friend's ice box and finding a single egg. Just an egg. Not another scrap of food. He took the friend home to dinner, but the bleak memory is still reflected when the television audience sees Kukla, beset by too many troubles, announce he is going to pack his little things and just go away.

The most significant part of that Summer was Burr's start in experimenting with hand puppets.

When Fall came, Burr was reluctant to put them aside, but he had won a scholarship to the University of Chicago and he felt it would be more practical if he should forget the stage and prepare to teach.

It might have worked if Burr hadn't fallen in love - devotedly, worshipfully in love with an ethereal ballerina of the Ballet Russe.

The feeling was quite different, he assures you, from his affection for his schoolmate girl friend. To Burr, Tamara Toumanova was the incarnation of the theater itself. As her Chicago engagement closed, he sought a parting gift to express his adoration.

Characteristically, Burr made a hand puppet. In Tamara's dressing room, with a chair back as improvised stage, he introduced his gift. Impishly, the puppet peeked up and bowed to the lady.

Tamara shrieked, "Kukla!" and began to laugh. "Kukla," she explained, was the Russian word for doll. It also was the Greek word and was used in most Slavic languages.

With his christening, the puppet seemed to take life. He danced, he bobbed, he pantomimed his eternal devotion to the ballerina.

Recalling that evening, Burr says, "It was the strangest thing - almost as though Kukla were doing it all himself. I suddenly found I couldn't bear to part with him."

Kukla was

disturbing. Burr was trying to be a serious

student. His marionettes were packed away, but he

couldn't ignore Kukla. Kukla wanted out. It

was, for Burr, a period of painful conflict

between two possible careers. In the

end, Kukla won. After two quarters, Burr quit

school and rejoined the marionette troupe. Show

business, he realized better than ever, was no bed of

roses, but it was the only thing he wanted to do.

Kukla was

disturbing. Burr was trying to be a serious

student. His marionettes were packed away, but he

couldn't ignore Kukla. Kukla wanted out. It

was, for Burr, a period of painful conflict

between two possible careers. In the

end, Kukla won. After two quarters, Burr quit

school and rejoined the marionette troupe. Show

business, he realized better than ever, was no bed of

roses, but it was the only thing he wanted to do.

The marionettes were the stars, and Kukla only a between-acts bit player. His personality did not emerge until the group scheduled an arty production of Romeo and Juliet. Burr wanted to play Romeo. He knew the role letter perfect. He ended up turning pages of the narrator's script, the most frustrated Shakespearean in Chicago.

Burr took his disappointment politely, but Kukla just couldn't stand it. Out he popped, during rehearsal, and in a voice which had its origin in Burr's old-man parts, he took up Romeo's romantic lines. He sighed for love and ranted against cruel fate. Then he shifted to do Juliet's role, too, interpolating highly personal comment on the cast. Things well-mannered Burr would never say, rattled rapid-fire from Kukla, and Kukla was a riot.

From that time on, Kukla became impromptu entertainer at all parties. People asked him questions, and as Burr says, "Kukla was really smart with people. When I was too young or ignorant to have an answer, Kukla took over. What would have been naive from me sounded funny coming from him."

It was 1938 before Burr's own personality developed sufficiently to give Kukla a companion. He was, by that time, getting a few bookings for parties, and usually his girl friend went along to help work the show.

She had a funny take-off on an opera singer. The voice was too good to waste, so Burr created Mme. Ooglepuss to match it. Even after Burr and his schoolmate sweetheart parted, Madame remained. Boasting of her great days, and cherishing the illusion she is irresistible to all males, she became a perfect target for Kukla's satire.

Ollie appeared shortly after Burr began his Saturday shows in the children's theater at Marshall Field's department store. Burr's mother played piano and kept the young audience quiet.

Traditionally, every puppet show had a terrifying dragon. Burr sought one which would not frighten the most timid child. The result was Ollie, possessed of one tired tooth, the gentle pop eyes of a heifer, and a foolish, bashful grin.

Ollie for some time, was content to stretch his neck and flap his mouth soundlessly. Then a friend of Burr's wrote "St. George and the Dragon," still a production pageant for the Kuklapolitans, and Ollie took voice.

Burr was playing the State Lake theater when it became apparent Mme. Ooglepuss needed a boy friend. Obviously Kukla wasn't going to stand still while she sang "My Bill" to him. From pure necessity, Burr created a new character who said the only thing one could say to such a woman, "Boyng!"

It wasn't until the show came to WBKB, years later, that Madame's tumble-tongued boy friend had a chance to get even. He asserted his independence by changing his name to Cecil Bill with a bow to the station's stage manager, Bill Ryan.

Cecil

Bill makes it clear his affections incline toward

Mercedes. Mercedes' origin was completely

commercial. A Marshall Field's official conceived

the idea of using the Kuklapolitans to dramatize sales

instructions to employees. Mercedes was invented

to show clerks how to cope with a nasty little girl and

add a few laughs to the problem.

Cecil

Bill makes it clear his affections incline toward

Mercedes. Mercedes' origin was completely

commercial. A Marshall Field's official conceived

the idea of using the Kuklapolitans to dramatize sales

instructions to employees. Mercedes was invented

to show clerks how to cope with a nasty little girl and

add a few laughs to the problem.

That was the cast in 1939 - Kukla, Mme. Ooglepuss, Ollie, Cecil Bill, and Mercedes - when an RCA unit moved into Marshall Field's and Burr Tillstrom discovered television.

Burr took one look at what happened with cameras and screen and knew it was for him. He pestered RCA and Field's officials, begging to go on. No one wanted him. At last, to silence the nuisance, someone gave permission and Kukla went to work. Officials were unimpressed.

Says Burr, "It was the engineers who saved us. They fell in love with Kukla. The guys who keep things running always like Kukla."

Their liking was contagious. Burr and Kuklapolitans were supposed to open the RCA exhibit at the New York World's Fair.

Their opener turned into an all-summer engagement. The Kuklapolitans had found their medium. Real to their creator, they became, when projected human-being size on a screen, equally real to their viewers.

Burr knew that come what may he had to stay in television. On his return to Chicago, he had just enough time to appear on some of WBKB's opening programs and play a show or two in the Zenith experimental studio before Pearl Harbor hit.

From

the services, Burr drew a flat footed rejection -

literally. He couldn't march, the Army and Navy

told him. His draft card was marked 4F.

From

the services, Burr drew a flat footed rejection -

literally. He couldn't march, the Army and Navy

told him. His draft card was marked 4F.

Bitterly embarrassed by looking so healthy and wearing civilians, Burr decided that even if the Navy would not have him, it might accept Kukla.

Out he went to Great Lakes Naval Training station to volunteer. His mother went along as accompanist, and the commandant equipped them with a tiny portable piano which could tour the hospital wards. The first of the casualties had just been returned.

Says Burr, "I never was so scared in my life. Here I was, a carefully preserved civilian, trying to be bright for a batch of guys who had caught hell on the beachheads. I wouldn't have blamed those Marines if they had thrown me out of the joint."

There were a few rough cracks while they were setting up for the first time, but the moment Kukla entered, the Marines took interest, and when Ollie showed up as a dopey Shore Patrol, they got their first real laugh.

"That," Burr recalls, "was when Ollie learned the value of the broad flag. Subtle nursery rhyme whimsey was out. Ollie got down to earth, and every time Kuke took off on some flight of fancy, Ollie grounded him, too."

It

was in the psychiatric ward that they won their

stripes. A wounded man was so deep in melancholia

he would not talk and was expected to die. In

desperation, doctors sent in Kukla and Ollie, warning

Burr anything might happen.

It

was in the psychiatric ward that they won their

stripes. A wounded man was so deep in melancholia

he would not talk and was expected to die. In

desperation, doctors sent in Kukla and Ollie, warning

Burr anything might happen.

The man wouldn't look, at first. Kukla and Ollie kept punching. He stole a glance. He watched. At last he smiled. The melancholia broke. A few weeks later, he was discharged from the hospital.

Every week for four years, Burr and his mother, Alice, brought the Kuklapolitans to Great Lakes, and the patients always said, "Come back again, Mac."

They worked bond shows, too, and it was there that Burr met Fran Allison. Fran was best known as Aunt Fanny, the gossipy old maid of Don McNeill's Breakfast Club.

In contrast to her public character, she is, in private life, the charming wife of Archie Levington, a song plugger with a music company. In relating their romance, Fran, who had come from Iowa to work in Chicago radio, says "Archie brought me a song to try. I sang the song, and I married Archie."

She fell in love at first sight for the second time when she met Kukla and Ollie. Like her own characterization of Aunt Fanny, they were real to her. She chatted happily and naturally with the pair.

Burr remembered this when, during the Fall of 1947, Captain William Crawford Eddy, then director of WBKB, asked him to do a children's show on the station. It would be an hour long, he stated and his old friends at RCA Victor ready to sponsor it.

Burr gasped. He had dreamed of this for years. Here was his chance, but it also was a chance to fall flat on his face. No one, Burr tried to explain, could do a new, hour-long, one-man show five times a week. He wouldn't even have the respite of music, for at that time Petrillo barred union musicians from television stations. It was, Burr pointed out, beyond all human endurance.

Captain Eddy, a fabulous character in his own right, believes nothing is impossible in television. He never batted an eye at Burr's protests.

"That's easy," said WBKB's Skipper. "Find someone who

can work with you out in front. Whom do you want?"

"That's easy," said WBKB's Skipper. "Find someone who

can work with you out in front. Whom do you want?"

Mixing puppets and people was unorthodox, but Burr took the challenge. He said, "Get Fran Allison."

It was a happy choice. Burr recounts, "Fran was just what we needed to turn our make-believe real. She's the Alice who wanders through Wonderland, the Dorothy who goes to Oz."

The same basic method of constructing a show, then as now, is this: After that spark of an idea comes, a plot is outlined within minutes and Kukla and Ollie take it from there. No one, not even Burr, is certain what will happen next and Fran must be alert to deal with the unexpected. That's why the show lives.

Kukla and Ollie turned out to be highly effective salesmen for new television sets, thanks to their friends. Every youngster who glimpsed the show was anxious to have his gang meet them. As word spread, Chicago's small fry scouted the town for receivers. An antenna on a roof was a standing invitation to come calling.

The mail that poured in expanded the Kuklapolitan cast. Obviously, the Kuklapolitans needed a mailman. Again Burr's childhood recollections supplied the answer. Fletcher Rabbit, who originated as a bit-player in Burr's version of Hansel and Gretel, was the choice.

To explain the workings of television to young fans, Burr also needed someone at home in the stratosphere. The Hansel and Gretel witch changed character. Burr freed her from her wicked heritage by giving her a small refresher course in sociology, electronics and aviation at Witch Normal, named her Buelah Witch and made her the expert on things televisual.

Another character came into being because Mme. Ooglepuss had not taken kindly to Cecil Bill's deflection to Mercedes, and Madame is not one to wither patiently. No one is quite sure where she found him, but she suddenly had in town an overly-courtly and slightly moth-eaten Southern gentleman designated as Colonel Cracky. That a real-life colonel was about to open a rival TV station then was purely coincidental.

It may

have been that Ollie was a little jealous of all these

new characters, for he began to make noises like an

oldest inhabitant. With family pride throbbing in

his dragonly throat, he went out of his way to talk

about his mother, whose ice-blue hair spun out behind

her when, in the old days, she sailed over Boston.

He spoke of how, after that certain unpleasantness in

Boston, when dragons, witches and their ilk were purged,

the family settled down to become substantial citizens

of Dragon Retreat, Vermont. Ollie was

spouting more genealogy than a D.A.R.

It may

have been that Ollie was a little jealous of all these

new characters, for he began to make noises like an

oldest inhabitant. With family pride throbbing in

his dragonly throat, he went out of his way to talk

about his mother, whose ice-blue hair spun out behind

her when, in the old days, she sailed over Boston.

He spoke of how, after that certain unpleasantness in

Boston, when dragons, witches and their ilk were purged,

the family settled down to become substantial citizens

of Dragon Retreat, Vermont. Ollie was

spouting more genealogy than a D.A.R.

It troubled Kukla. He never speaks of the lovely ballerina who gave him his name. He may, via television, be into the Everywhere, but to him, his origin is lost in Nowhere. Wistfully, one day, he wondered out loud about it. Fletcher, said Kukla, was a rabbit, Buelah was a witch, Ollie a dragon, but what was he?

A little girl visiting the show that day had an answer. She had, she said, asked her mother about it. "Mother says," she piped, "That you're a blessing."

That's good enough for Kukla, for Burr and the other people concerned with the show. From then on, they all designated Kukla as "a blessing."

This fall, Burr, who has not forgotten what RCA and NBC did for him in the lean days of television, has moved over to WNBQ, the NBC outlet in Chicago. The million-dollar contract notwithstanding, Burr remains an impressively modest guy. His original hat, if he ever wore a hat, would still fit. He lives with his parents in a comfortable, but not pretentious apartment on the north edge of Chicago, near Evanston.

His day, customarily, starts around ten o'clock when he pries his eyes open, wrestles on a white terry cloth robe and stumbles into the kitchen where his mother has breakfast ready. He's slow to wake up, he confesses, and his mother usually accomplishes the feat by turning on a wire recording she has made of the previous night's show.

Burr listens as he eats, interrupted now and then by a dive-bombing tiny green parakeet, who can say his name, "Buster Tillstrom," and also the name of Burr's sponsor. He hasn't, Burr insists, yet discovered he is a bird. Like Kukla and Ollie, he thinks he is real.

Breakfast finished, Burr usually contrives to spend an hour or so in his workshop where he makes props for the show. He's a skilled craftsman, thanks to his WPA theater days. The miniature gadgets you see Kukla and Ollie employ have usually been constructed by Burr.

Dr. Tillstrom's arrival is his signal it's time to quit the shop. The family lunches together, and then Burr leaves for Loop business appointments.

By three o'clock he reaches the studio where he confers with Jack Fascinato about music, talks with his friend Joe Lockwood - Monsieur Josef - about costumes, and dictates answers to fan letters. Then Fran arrives, Beulah Zachary and Lew Gomavitz, the producer and director come in and the plot huddle starts. Some one says, "Now why doesn't Kukla take the company on a tour of the Caribbean . . ." And they're off. A couple of hours later, televiewers are seeing it happen, right on the air.

There isn't, at the present time, any super-important girl in Burr's life. Every time some publication mentions he is unmarried, proposals come in. Burr is indifferent to them. He's sure they are meant for Kukla, not him.