FRAN ALLISON is a charming ex-school-teacher from Iowa who ranks with Hopalong Cassidy and Milton Berle among the phenomena of television. However, Fran does not ride a horse like Hopalong or make with jokes like Berle. She talks to a non-fire-spitting dragon named Ollie.

Ollie is a puppet dragon with one cotton tooth, and he has a wistful puppet pal, Kukla, who also takes part in the coaxial conversations with Fran. In the last six months, their Kukla Fran and Ollie show has become one of the hottest fireside entertainments since popcorn.

Upward

of 5,500,000 video sets per week are channeled in on

their five half-hour

programs of song and whimsey over the National

Broadcasting Company network.

And not only children stop, look and listen to K. F. and

O. Adults

find the life-like dolls with the real-life doll just as

fascinating.

The fan mail of this Monday-to-Friday show tops 6,000

letters a week - plus

some astonishing gifts. For example, a Brooklyn dentist

sent Ollie a set

of false teeth. Kukla's admirers have contributed 79

potatoes of varying

sizes, all of which resembled him, and some of which

(Ollie insisted) were

down-right flattering.

Upward

of 5,500,000 video sets per week are channeled in on

their five half-hour

programs of song and whimsey over the National

Broadcasting Company network.

And not only children stop, look and listen to K. F. and

O. Adults

find the life-like dolls with the real-life doll just as

fascinating.

The fan mail of this Monday-to-Friday show tops 6,000

letters a week - plus

some astonishing gifts. For example, a Brooklyn dentist

sent Ollie a set

of false teeth. Kukla's admirers have contributed 79

potatoes of varying

sizes, all of which resembled him, and some of which

(Ollie insisted) were

down-right flattering.

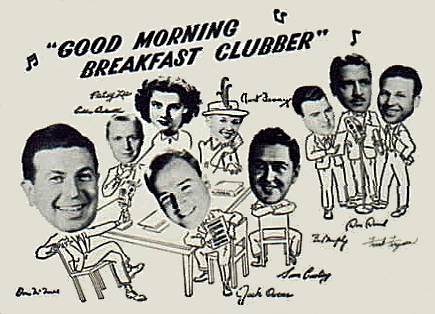

So far, Fran has not been deluged with dentures or garden produce. Shortly after Christmas, however, a lady from Peoria walked right past Charles Boyer without a side glance, so intent was she on getting Miss Allison's autograph. The incident did things for Fran's morale, which had been pretty badly deflated by 10 highly anonymous years in Chicago radio. During this bleak period she suffered interminably in soap opera, trilled singing commercials and portrayed a good-natured old gossip named Aunt Fanny on Don McNeill's Breakfast Club.

Aunt Fanny once told her listeners that she was around twenty-five years old, then added, "Course, it's the second time around." Actually, Fran is much younger than she makes Aunt Fanny sound. She has piquant colleen features, black hair, blue eyes and a willowy figure. Along with all this, she has a quick tongue which is thoroughly at home in almost any dialect or situation. She can ad-lib with anybody - even Burr Tillstrom, Ollie's ambidextrous and multivoiced employer.

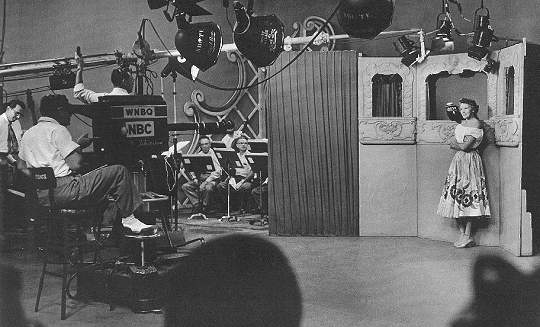

The charm of Kukla, Fran and Ollie is its unrehearsed, scriptless spontaneity. One evening a few weeks ago, Fran and Burr walked into their tiny studio in Chicago's Merchandise Mart at three minutes to six, Central standard time. Fran looked glamorous in a brown corduroy skirt and a red blouse. Tillstrom, a slender young man with a crew haircut, who was clerking in a department store a few years ago, looked comfortable in his usual work clothes - white T-shirt and slacks.

Director Lou Gomavitz, in the control room, made a quick light-check on Fran's blouse as she moved over to the puppet stage in front of the cameras.

"Okay,

it makes a good picture." he said. Then: "Sixty seconds

- quiet, everybody."

"Okay,

it makes a good picture." he said. Then: "Sixty seconds

- quiet, everybody."

"Time to go to work," Burr Tillstrom murmured. He eased around behind the stage and reached for a round-nosed puppet. "Hello, Kukla," he said, slipping the puppet over his right hand like a glove. "Where's Ollie?"

"Hanging on the wall," he answered with Kukla's voice, a wistful falsetto.

"Thanks, Kukla." Tillstrom's left hand reached up and came down enclosed in the form of a small and rather handsome dragon. "You feeling all right. Ollie?"

"I feel wonderful," Ollie replied in a throaty baritone which also belonged to Tillstrom.

"That's good. I have a hunch you're going to need all your strength for this show."

Out front in the studio, the announcer finished the opening commercial - the show's current sponsors are Sealtest, Ford Motors and RCA. And then Kukla, Fran and Ollie was flashing along the coaxial cable.

Kukla popped up on the tiny stage and called out, "Fran."

"Coming." Fran moved into camera range, standing just to the left of the stage, almost cheek-to-cheek with Kukla. "Goodness!" she said. "You look worried. What's wrong?"

"It's

Ollie," Kukla explained. "He went shopping at four

o'clock. Said

he needed a new pair of rubbers. And he hasn't

come back yet."

"It's

Ollie," Kukla explained. "He went shopping at four

o'clock. Said

he needed a new pair of rubbers. And he hasn't

come back yet."

"I wouldn't worry about him," Fran soothed. "Ollie knows how to take care of himself."

A telephone rang. "I'll get it," Kukla said. He disappeared below stage, bobbed up again holding a receiver. "Hello."

"Kook," said an out-of-breath baritone, "this is Ollie."

"What happened?"

"Something awful - I got stuck in an escalator."

"Where are you now?"

"Glockenspiel's bargain basement. I had to stand in line 10 minutes to get to this phone. Honestly, Kook, the way these women push and shove. Madam" - Ollie's voice deepened indignantly - "Madam, please!"

The line went dead.

Kukla turned to Fran. He sighed, "Well, I guess they

trampled poor old

Ollie."

Busy Dragon Gets Lots of Sympathy

Poor old Ollie! At that moment, TV fans sitting before more than 17 per cent of the television sets switched on in America - an amazingly high percentage - were sympathizing with the tiny dragon's unseen plight. Ordinarily, people do not worry much about what happens to dragons, but you can't help worrying about a friendly, hard-working character like Ollie, who is fond of buttered popcorn and occasionally puts his hair up in curlers. He also edits a newspaper, punching out copy on a typewriter with his tooth. In addition, Ollie works tirelessly to improve his diction, repeating over and over in pear-shaped tones, "Gloria, come back. I can forgive but never forget."

Now, all this may sound fantastic - almost as fantastic as a dragon shopping for rubbers in the basement of Glockenspiel's department store - but it doesn't seem that way to Ollie's friends. They believe in Ollie, probably because Fran believes in him. Her warmth and kindliness work a sort of Alice-in-Wonderland magic, which transforms a television screen into the Looking-Glass, and makes Tillstrom's cloth-and-cotton puppets as real and believable as the Walrus or the Red Queen.

When

Kukla and Ollie are occupied elsewhere, Fran sings a

song, or visits with

the other Kuklapolitan puppets who inhabit Tillstrom's

Wonderland: Fletcher

Rabbit, the mailman who starches his floppy ears; Madame

Ophelia Ooglepuss;

the haughty retired opera singer; gallant Colonel Cracky

of the deep South,

who calls every woman (even Madame Ooglepuss) his

fragile magnolia blossom;

Beulah Witch, who patrols the air on a gold broomstick;

beautiful-but-dumb

Clara Coo Coo; Mercedes, a very naughty girl, and

stagehand Cecil Bill, who

speaks a language only Kukla understands.

When

Kukla and Ollie are occupied elsewhere, Fran sings a

song, or visits with

the other Kuklapolitan puppets who inhabit Tillstrom's

Wonderland: Fletcher

Rabbit, the mailman who starches his floppy ears; Madame

Ophelia Ooglepuss;

the haughty retired opera singer; gallant Colonel Cracky

of the deep South,

who calls every woman (even Madame Ooglepuss) his

fragile magnolia blossom;

Beulah Witch, who patrols the air on a gold broomstick;

beautiful-but-dumb

Clara Coo Coo; Mercedes, a very naughty girl, and

stagehand Cecil Bill, who

speaks a language only Kukla understands.

The Kuklapolitans divide their time rather evenly between gossiping with Fran and putting on plays. Kukla usually sings the romantic leads in their adaptations of musical hits like Brigadoon and High Button Shoes. Ollie, who is something of an extrovert, prefers meatier melodramatic parts. The robust manner in which he played Ferdinand to Fran's Isabella last Columbus Day was acclaimed the outstanding performance by a male dragon of the 1949 theatrical season. In addition to being Ollie's leading lady at night and Aunt Fanny in the morning, Fran has a fulltime job as the wife of Archie Levington, a Midwestern song plugger. They live with Fran's mother Nan, on Chicago's fashionable near North Side.

Nan, in her early seventies, has been Fran's adviser and consultant ever since Grandfather Allison secured his grandchild's first professional engagement at a meeting of the G.A.R. of Black Hawk County, Iowa.

"What'll I sing, Mom?" asked Fran, who was then four years old.

"I think," Nan decided, "you better try Little Boy Blue,"

Nan

also gives Aunt Fanny an occasional colloquial

assist. Once, when Fran

needed a pithy description of a neighborhood gossip, Nan

suggested, "There

was a woman back home who was just about the talkingest

person I ever met.

She could stay longer in half an hour than anybody else

could in a whole

afternoon."

Nan

also gives Aunt Fanny an occasional colloquial

assist. Once, when Fran

needed a pithy description of a neighborhood gossip, Nan

suggested, "There

was a woman back home who was just about the talkingest

person I ever met.

She could stay longer in half an hour than anybody else

could in a whole

afternoon."

Away from microphones and cameras, Fran is a good country-style cook. She dabbles with Mexican dishes, but sticks to steak and potatoes when she's really hungry. For relaxation, she reads mystery stories and listens to the radio, simultaneously. She can leaf through a Perry Mason adventure while absorbing The Road of Life without missing a clue or a heartthrob.

Fran

often listens to soap opera for two or three hours at a

time, while Archie

keeps himself occupied in his basement workshop.

"She isn't interested

in the stories so much," Archie says morosely.

"She has a lot of friends

working in New York soap opera and she likes to keep

track of the way they

shift from character to character."

How Monologues Originate

These days, on Breakfast Club mornings, Fran gets up at six o'clock, has a cup of coffee with Nan, then spends the next two hours nibbling hot buttered toast and mulling over ideas for her Aunt Fanny monologues. Invariably, the best ideas grow out of her own experiences.

When

she returned to the program after an appendectomy,

master of ceremonies McNeill

said, "Well, well, it's good to see you again, Aunt

Fanny. Did the

doctors find out what you had?"

When

she returned to the program after an appendectomy,

master of ceremonies McNeill

said, "Well, well, it's good to see you again, Aunt

Fanny. Did the

doctors find out what you had?"

"No," Aunt Fanny replied tartly, "but they came within three or four dollars." Fran never uses a script - merely jots down a few cue words on the back of an envelope.

Aunt Fanny taxies home from that show and becomes Mrs. Levington again. She reads the morning papers, has an early lunch, takes her daily pounding from a masseuse, naps until three o'clock, then taxies back down to Kukla, Fran and Ollie headquarters at the NBC studio.

At four o'clock, Tillstrom outlines the program in a story conference with Fran, director Gomavitz, producer Beulah Zachary and musical director Jack Fascinato. Nothing is written down. "If I ever plotted exactly what I was going to say or do," Tillstrom explains, "Kukla and Ollie wouldn't work for me. They don't like cut-and-dried stuff. Fran wouldn't be able to talk to them, either. After all, you don't need a script when you're talking to your friends."

For more than two years, and in nine different voices, Tillstrom has been trying to catch Fran off guard, but he has never quite succeeded. For example, take that last Columbus Day show. Ferdinand (Ollie) greeted Isabella (Fran) in rhyme.

"Hello, Iz," he said, "how's biz?"

"Why, Ferd," she exclaimed, seemingly amazed, "haven't you heard?"

"Well," Ollie conceded, stepping out of character, "you win that round." He retired in confusion, and Kukla - only partly dressed - had to rush on stage and clamber aboard the Santa Maria three minutes ahead of schedule.

After saying good night to Kukla and Ollie, Fran meets husband Archie for dinner, and they round out Fran's eighteen-hour day by visiting three or four supper clubs before starting home around midnight. It's business for Archie, who has to keep up his contacts with singers and band leaders, and pleasure for Fran, who knows almost everybody in show business.

How Fran broke into radio is a rather complicated story. After completing her musical studies at Coe College in Iowa in the spring of 1927, she had no trouble whatsoever finding a job selling sheets and pillow cases in a Davenport department store. Finding a job singing was something else again. A few church choirs were mildly interested, but not to the extent of offering her a salary. Reluctantly, in the fall, Fran went to work teaching rural school at Schleswig, Iowa.

After

four years of teaching - in Schleswig and Pocahontas -

Fran received formal

notification that her salary was to be increased from

$100 to $102 per month.

Deciding that progress was too slow at teaching, she

invested a portion of

her savings in a trip to Kansas City where, according to

a newspaper advertisement,

a "wonderful opportunity" awaited young women with

dramatic talent.

After

four years of teaching - in Schleswig and Pocahontas -

Fran received formal

notification that her salary was to be increased from

$100 to $102 per month.

Deciding that progress was too slow at teaching, she

invested a portion of

her savings in a trip to Kansas City where, according to

a newspaper advertisement,

a "wonderful opportunity" awaited young women with

dramatic talent.

This opportunity, it developed, was a two-week course in play producing: matriculation fee, $50. Fran was graduated with highest honors, two trunks containing an adequate supply of white muslin shrouds and other basic production equipment for a drama entitled Ghost House, and a one-way bus ticket to Carthage, Missouri.

"Down in Carthage," explained the dean of the Kansas City school, "there's an orchestra that's trying to raise some money. They'll sponsor your play and provide local amateur talent. You direct and produce and we split the profit - 60 per cent for the sponsors, 20 per cent for us, 20 per cent for you."

Fran worked a month in Carthage to earn $21.60. Then during the next three stops her show lost money. The inevitable telegram finally arrived: NO FURTHER ASSIGNMENTS AVAILABLE. She took the long bus ride home to La Porte City, Iowa, arriving on Thanksgiving Day with 50 cents and her battered production trunks. Next came low-paying singing jobs at radio stations in Cedar Rapids, Ottumwa and Waterloo.

One summer afternoon in 1934 at Station WMT in Waterloo, announcer Joe DuMond - desperate for material to fill out the last three minutes of his Cornhuskers program - spotted Fran in the audience. "Well, well, folks," DuMond ad-libbed, "guess who just dropped in - Aunt Fanny! Come on up here, Aunt Fanny, and tell us what's new."

Startled, Fran did a take-off on a good-natured, garrulous spinster she had once met. "Well, Mister DuMond," she said, "I dropped by to see Daisy Dosselhurst yesterday and her Junior came to the door and I said real nice, 'Junior, is your mother home?' 'No, she ain't,' he said. 'Is your father home?' I asked. 'No, he ain't,' he said. Well, I had heard about enough ain'ts, so I said, 'Where's your grammar?' He answered quick, 'She ain't here, either.'"

It was a pretty bad joke, but the way Aunt Fanny told it made it sound pretty good. After that impromptu skit with DuMond, Fran created her bread-and-butter character out of the old maid. After a few more guest appearances, Aunt Fanny became a daily feature and Fran landed her first sponsor - a Waterloo firm which manufactured heavy farm equipment.

Future Husband's Bad Guess

Miss

Allison finally broke into network radio in the summer

of 1937 by auditioning

successfully for a staff singing job with NBC in

Chicago. The tryout

was arranged by Bennett Chapple, a man to whom Fran is

eternally grateful.

Archie Levington, who heard the audition, made a

monumentally poor guess

when asked to estimate Miss Allison's

possibilities. Unaware that he

was speaking of the woman he would someday marry, Archie

declared, "Give

her six months - then back to Waterloo."

Miss

Allison finally broke into network radio in the summer

of 1937 by auditioning

successfully for a staff singing job with NBC in

Chicago. The tryout

was arranged by Bennett Chapple, a man to whom Fran is

eternally grateful.

Archie Levington, who heard the audition, made a

monumentally poor guess

when asked to estimate Miss Allison's

possibilities. Unaware that he

was speaking of the woman he would someday marry, Archie

declared, "Give

her six months - then back to Waterloo."

Despite this dire prediction, Fran managed to keep busy in her own anonymous way. She was the first girl vocalist on Breakfast Club. She co-starred, with Grandpa Putterball on Sunday Dinner at Aunt Fanny's, and disguised Aunt Fanny as Fanny Pettingill on Uncle Ezra's program. She substituted expertly for the front third of Clara, Lou and Em, and demonstrated her versatility by playing a cousin on Those Websters, a mother in the Peabody series, and the sister in Cousin Myrtle and Sister Emmy.

Between programs Fran carried on a rushing business in singing commercials, partly because she could sing in one key and whistle in another a rare talent which permitted the perpetrators of the commercials to work out a variety of special effects without doubling the pay roll.

In

1942, six months before Archie went into the Army as an

infantryman, he and

Fran were married. While Archie was overseas Fran

went on War Bond

selling tours in the role of Aunt Emmy, and worked with

entertainment units

playing Midwestern hospitals. She met Tillstrom,

4F with two flat feet,

and Kukla and Ollie one day at Great Lakes Naval

Training Center, where Tillstrom

was putting on a puppet show in the wards. Fran

and Ollie, with an

assist from Tillstrom, got to talking while waiting for

the show to start

and discovered they had a lot in common.

In

1942, six months before Archie went into the Army as an

infantryman, he and

Fran were married. While Archie was overseas Fran

went on War Bond

selling tours in the role of Aunt Emmy, and worked with

entertainment units

playing Midwestern hospitals. She met Tillstrom,

4F with two flat feet,

and Kukla and Ollie one day at Great Lakes Naval

Training Center, where Tillstrom

was putting on a puppet show in the wards. Fran

and Ollie, with an

assist from Tillstrom, got to talking while waiting for

the show to start

and discovered they had a lot in common.

Pretty soon Fran was spluttering away in her Aunt Fanny dialect, chatting merrily with Ollie. Ollie enjoyed talking with Fran. So did Tilistrom. He remembered it one October afternoon in 1947 when Captain Bill Eddy, then director of Chicago Television Station WBKB, asked him to put together a puppet show for children.

"I couldn't do it by myself," Tillstrom protested, when he learned it was to run five afternoons a week. "It's too much work."

"I'll get you all the producers and writers you need," Eddy promised.

"What would I do with writers?" Tillstrom asked. "With my hands full of puppets, I couldn't read a script if I had one."

"Well, what do you need?"

"A girl to work out front. Somebody who can interview guest stars - sing a song now and then." Tillstrom thought for a moment. "I guess what I really need is a girl who can talk to a dragon - say, do you know how I can get in touch with Fran Allison?"

THE END